Ibn ʿArabī is a celebrated Muslim scholar in the Islamic community, primarily on the cosmic script of the Arabic alphabet. His magnum opus, The Meccan Revelations, inspired Dr. Dunja Rasic to study how basic letters can unleash their own spirits and consciousness. She joins Debra Graugnard and her co-host Amany Shalaby to discuss her work around Arian cosmology, philosophical sophism, and language guided by Ibn ʿArabī’s works. Dr. Dunja explains how every Arabic letter has its own properties that go beyond forming words but also impacts emotions, spirituality, and the entire flow of the universe on every individual. She also talks about the right approach in addressing contradictions happening between science, religion, and art that lead to a more meaningful path of understanding.

—

Listen to the podcast here

The Written World Of God With Dr. Dunja Rasic

In this episode, we have Dunja Rasic. Welcome, Dunja.

It’s a pleasure to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

I’m excited about this interview. I don’t know if there is any way to be completely prepared for this, but we’ll see where it goes. I’m going to begin by reading your bio and then we’ll begin with our questions for you.

I’m delighted to see where this is going to go. Dunja Rasic earned her PhD in Islamic Studies at the Free University Berlin. Her primary research field is Medieval Intellectual History with focused on Akbarian Cosmology, Philosophical Sufism, and the Islamic Philosophy of Language.

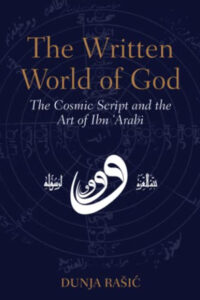

She is working on her second book, which is focusing on jinn doubles and the problem of evil in Akbarian Sufism. Let me add that her first book is called The Written World of God: The Cosmic Script and the Art of Ibn ‘Arabi.

I have been making my way through this book. I will admit that I have not completed it, but it is an amazing study that I love. I feel like a student who’s not quite prepared for the exam but very excited to dive into it.

I want to also welcome my cohost, Amany Shalaby. She was my translator for my spiritual teacher for the last twelve years of his life, Shaykh Muhammad al-Jamal of Jerusalem. Amany has her Master’s in Comparative Philosophy of Religions and her Postgraduate degree in Islamic Studies and Sufism.

She is a Founder of Universal Chaplaincy, and I have gone through her chaplaincy program. She’s also a co-teacher in the program The Ocean of Sound. Welcome, Amany and Dunja. I’m very excited. Thank you. Nice to meet you, Dunja, and it’s a pleasure to have you with us. It’s very exciting. I would like to know what sparked your interest in the Ibn Arabi cosmology of the letters. What inspired you to start that study of the Akbarian world?

It feels that it began almost a lifetime ago when I was an aspiring student working on gaining my bachelor’s degree in Islamic studies at the University of Belgrade. I was not yet a member of Ibn Arabi Society, but in Ibn Arabi Society, we are often reminded that we are standing on the shoulders of giants. It was one of these giants.

It was the work of Professor William Chittick that first introduced me to the topic. It is now a classical work in the field that self-disclosure of God, the principles of Ibn Arabi. In the introduction to this book, he described one of his abandoned projects. It began with a simple idea, which is to introduce the structure of the nature of the universe, The Act of Genesis. To summarize, Ibn Arabi’s teachings is best as one could by speaking only about the letters of the Arabic alphabet.

This abandoned project was to be based on Chapter 198 of Ibn Arabi’s magnum opus, The Meccan Revelations. This got me to read The Meccan Revelations in Arabic for the first time. It was also then that I discovered that Chittick abandoned this project. Although I searched, there was next to nothing to be found on the topic back then.

It was long ago. I was still a backfill student. It did not occur to me yet that I will one day be getting a PhD degree in Islamic Studies. At that time, I will be setting up this task myself to write this book that I wanted to read for a long time, but I couldn’t because it was, at that point, to be written.

You started your journey from there of studying that work and then decided to write this work that is the first book you wrote. How that came about?

It was not a direct journey. It was an idea that was rooted in my mind, but I ended up doing my PhD dissertation on a very dry, regular, and boring topic, plainly speaking. I submitted my doctoral dissertation in 2018. I was still pondering where to go from that point. I did not seriously consider dedicating myself to Akbarian studies truly and completely until that point.

The starting point for me was a journey in Algeria. I had the pleasure of spending two weeks at the Zawiya of the Sufism Sheik Sidi Ahmad Tijani who generously decided to host participants of the Perennia Verba Summer School on Sufism.

I did my Master’s thesis on Ibn Arabi. If there are coincidences in this world, I applied by mere coincidence, but it was the conversations and long hours of discussions with Sufis of Tijani in Zawiya and other members of Perennia Verba summer school that directly and irrevocably pushed me in this direction.

I also got two valuable gifts from the sheik himself to help me with my journey. One of those gifts was Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyya in Arabic. Another gift to help me proceed was a piece of calligraphy. I call it a piece of calligraphy, though it was a talisman in the Akbarian sense of the world.

It was a copy of the Surah Al-Fatiha, which was supposed to protect me and help me as I proceed on this journey of finalizing the topic that Ibn Arabi himself insisted as dangerous and can result in debt, madness, and loss of reputation for the uninitiated. The true start of the journey was in late-2017 and 2018. That is when I truly started to work on this book. I have been an aspiring scholar in Akbarian studies ever since, hoping to proceed in this direction in the years to come.

I appreciate that if I can jump in there. One of the questions that come to me in diving into this study myself and wanting to learn more about it is how much of this you can understand without having some divine intervention to guide you along the path of understanding.

Ibn Arabi’s fear was that we can understand very little. It was one of the greatest joys of this research, which is to discover the art of Ibn Arabi. The surviving diagrams are in the hand of Ibn Arabi himself because Ibn Arabi insisted that the science of the letters is a prerogative and privilege of God’s friends and God himself. Even the knowledge of the letters is very difficult to convey to the uninitiated.

As a result, Ibn Arabi realized complex diagrams in his works, which were supposed to help people comprehend his knowledge because he said, “We all have imaginal faculties. We all have the power of imagination, even if our spiritual and rational capacities are limited.”

We all have the power of imagination even if our spiritual and rational capacities are limited. Share on XEven though we cannot immediately comprehend his teachings, contemplating his diagrams might help us proceed with the quest for knowledge. It was great joy and honor for me to be able to assemble all surviving diagrams Ibn Arabi sent and publish them for the first time. That was one of the most interesting parts of the process for me of the writing.

Was there a sparking moment when you were looking at one of the diagrams that open for you a way of understanding? I remember years ago, I tried to read Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiya in Arabic, which is my native language. I found it very difficult to understand.

A few years ago when we started the program about the sound, all of a sudden, something sparked me to open, to look deeper. All of a sudden, as I read Arabic, I started to understand some of the concepts which I was not able to understand before. Was that true for you too when a certain diagram or certain sentence opened it for you to dive deep and understand it, and what was that, if you can share with us?

It is a familiar feeling. If the spark ever came, it was subtle. It is as Ibn Arabi said, “If you read the text of the Quran, and it appears to you that one word has the same meaning as the day before, you are doing something wrong. If it happened, it was a subtle or a change.”

I read it daily or regularly, Ibn Arabi’s work, especially Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyya, and I always find new layers to familiar topics. The book always yields a bit more day after day. I’m not assuming or presuming that I have come to the bottom of the topic of the letters if that is even possible.

Such topics are akin to what the Quran Ibn Arabi says. They are the ocean without a shore. For example, the calligraphy of this Fatiha that I received as a gift from the Zawiya. When a calligrapher refused to elaborate on the specific properties of his work, Ibn Arabi and Sufis, in general, insist that letters get their specific properties not just from their spirits but also from the orthographic forms.

For the sake of fairness, a day later, the calligrapher did one present for each participant of the summer school, but only mine had letters that were curving upwards like spirals. It’s very akin to cosmological diagrams Ibn Arabi himself was a painting.

I look at this calligraphic piece daily, and I haven’t figured it out. I am hoping one day to come to the bottom of it too. It was my first encounter with applied letters of Sufi attempting to use the powers of letters to achieve a certain goal. In this case, it’s to use them as a blessing and as a protection.

Can you, in layman’s terms, give the basic idea of letters as having their own spirits, their own consciousness, and how they go beyond communicating words that so many of us take language for granted?

At the core of it is a general idea that when Sufis like Ibn Arabi writes about existence, they write about the three great books, the Holy Quran, The World, and Human Beings. Ibn Arabi believed that the whole world was created when God pronounces a single word. That is kun, which is to be. The idea comes from the Quran where several verses are read when he wishes for something to be.

He says, “To that thing be,” or kun. There are Sufis who believe in the creative word of God. Kun has 28 meanings corresponding to the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet, which then correspond to the 28 levels of existence. For example, God speaks or whispers a letter, and a thing steps into existence.

The idea might be a bit difficult to explain shortly, but Ibn Arabi speaks of the creative force as the Breath of the All-Merciful, nafas ar-rahman. He compares it to a human breath. He fully identifies this act of breathing with the act of speaking.

When we would explain that by focusing on human anatomy, we could say that breath is a prerequisite not just of life, but also speech. One inhales, the air travels to the human articulatory system, and where the air is blocked by articulatory organs, a sound forms.

He fully identifies the act of breathing with the act of speaking, and the properties of speech influence what will be created. Once again, to explain it metaphorically, human words have certain impacts. They can trigger some emotions in people around us. They can cause some things to happen. It functions in a similar way.

He divides the letters of the Arabic alphabet or distinguishes between spoken letters, written letters, and the so-called letters of power. Human speech has a short-term effect. The written words and texts could have a longer influence and impact on the world around us, but friends of God also have access to the so-called letters of power.

Letters are even viewed with the so-called energy or Hima, the spiritual power, which can then be used to cause specific long-term impact in the world around us, even if the text in question is destroyed, which was the intention behind the present that I got at Zawiya, Tamasi. That’s the so-called applied letter.

It’s a lesser-known aspect of Ibn Arabi’s teachings. It was also a source of encouragement for his students and followers in the centuries to come. Ibn Arabi himself used to make talismans which focus powers based on letters and the properties of the letters of the Arabic alphabet. There are surviving talismans or one surviving talisman in Ibn Arabi’s hand, which is the manuscript of Kitab al-ghayat which is being kept in Turkey.

When I dive into his work, all of a sudden, it became clear to me at one point, not all of it because it has no bottom as we said. When he said that the world is created of 28 letters, because my background is in Physics and Engineering, I found that the elementary particles, you can compare them to the letters.

If you found the subatomic particles, then you end up with vibration. A vibration is we find the audible range as a certain spectrum of this vibration, but there is cosmic vibration. Somehow our speech is in harmony with that.

I used to be skeptical of the talisman. We grew up in the Islamic culture looking down at these things as unscientific. All of a sudden, I could understand that it carries the energy of the one who speaks. As you said, words may affect us emotionally, may make us cry, raise our blood pressure, or make us happy.

In a way, this talisman carries the energy of the one who spoke them and can have an effect. Have you come to understand the meaning of one particular letter and its effect, or did you come across Ibn Arabi who spoke about all the letters? Have you come across one of the letters that opened for you a little deeper understanding, and what was that if you would like to share it with us?

The question is a bit complex. In my book, I go through all of the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet, their meaning, and properties. It is truly, as you said. Ibn Arabi himself also compares letters to elements and particles. Let’s speak figuratively in modern terms. Although the number of chemical elements is limited, they can form countless numbers of combinations.

It is the same with letters forming words. The letters of the Arabic alphabet, even Ibn Arabi said, have different properties in their isolated forms when they are on their own and when they are used in combination with other letters.

I wrote on the properties of each of the letters in their isolated forms, but when we speak about the combination of letters, the one of them that I studied also in my book is Alif Lam Mim, the disjointed letters from the Quran. Ibn Arabi relied on the properties of these letters to write his only surviving talisman, which we still have.

It’s supposed to harness the properties of these three letters. What exactly Ibn Arabi wanted to achieve with this talisman remains unclear, but we know relatively few things about the symbolism of the disjointed letters Alif Lam Mim, which were among other things meant to explain the relationship between God and the world or between the creator and the created to convey the general idea that God provided humans with signs leading them back to him with the signs on the horizon and signs in their souls.

This is something Ibn Arabi insists on. The world of nature is filled with these signs for those who have eyes to see that even the movement pattern on worms in the ground can lead those who pay attention to knowledge, to their God, and to whatever they are aspiring for.

We are all given different passions and things to explore in the world. As you say that, I get a visual of all of the roads of whatever passion you are given to what you are aspiring, whether you are studying the worms in the ground, the stars in the sky, or the letters. They all have the power and ability to lead to the knowledge of God.

That’s the Akbarian idea that the world is filled with science that it is rich with meanings and that it has great depth. In this regard, there is no mountain that can compete with a grain of sand. The problem is not that humans choose not to look. Ibn Arabi also insisted that another problem is that they are selective.

Where will they direct their gaze? God appears everywhere, even in the ugly face of a Jinn, a spirit of fire, or the animals that appear ugly to human eyes. This is something Ibn Arabi insist on in the very first chapter of The Meccan Revelations that ugly things can lead to beautiful outcomes sometimes if we are only willing to look at them for long enough.

He also says that things are relative, which regards beauty. The human notion of beauty is relative because when we speak in absolute terms, the whole world is beautiful because his face is reflected everywhere because God is everywhere. That is the basic idea.

The human notion of beauty is relative. In absolute terms, the whole world is beautiful because God’s face is reflected everywhere. Share on XI don’t know who worked on the cover of the published book for you, but I see that it’s distinguished. I know from my reading that Zawal is very special or has a special status. Can you talk to us a little bit about that?

I will not take credit for the design of the book. Authors and academia have, in general, very little say on the matter. I can only speak for my own reasons why I approve of this cover and the reasons why I like it. The reason why the letter involved can be considered someone special in Akbarian Sufism. It is a love letter. It is pronounced at the human lips at the far end of the human vocal tract.

In order to reach the lips, the air must pass to the whole vocal tract from the lungs all the way to the lips. Ibn Arabi believes that the letters also get their properties from the places of pronunciation. As the air must pass through the whole vocal tract, Ibn Arabi took this as the indication that the letter involved somehow possesses the properties of all other letters.

Hence it was considered someone special in Akbarian Sufism. In its isolated form, it also stands for the step levels of spiritual development. It is a symbol of a spiritual journey of a seeker. This is also dear to me, and this is why I chose to approve this cover, which is also aesthetically beautiful.

If I may have a follow-up with that, that is powerful what you said that it has the collection of all the letters because it passes through on the vocal tract. It’s in Arabic. It’s used to mean and, the Al-Jaami. It’s like collecting or assembling everything together. From my studies also, Zawal is a symbol of the golden ratio, the Fibonacci, like the spiral. It has a special place because of that. Is any other special letter that you can share with us some knowledge about?

Each letter is special in its own way. I’m looking into the letter Alif. The letter Ibn Arabi says is not a letter due to the fact of what it stands for. Alif stands for the divine essence, or in other words, for the nature of God as he is before he created the world. Even the mere act of thinking about the divine essence, and thus, the letter Alif can be considered a luxury of thinking.

The reason why I am looking into this letter is that Ibn Arabi repeatedly compares it to the standing position in prayer or for a human being who stands. The standing position in Akbarian Sufism is usually not generally looked upon in a favorable way because a standing human appears so tall, proud, and independent. The human Ibn Arabi insisted closer to God as they prostrate to the ground in prayer.

However, standing and especially standing during the night, performing night rituals was considered somewhat special in Akbarian Sufism and closely associated with the certain type of perfect humans, which are the highest step level human beings can reach. I’m researching the letter Alif in that regard as a symbol of humans, the lover, who is completely and absolutely focused on the divine beloved.

I’m hoping to develop perhaps a new book, a new research on the so-called night folk of people who pray during the night and withdraw themselves from the world and for whose sake God created the night because he loved them so much that he decided to hide these special perfect humans from the world so that he could have them all for himself. I’m hoping to soon produce a new book on the night vigils, the symbolism of the night, and night prayers in the Akbarian context with regards to the letter Alif.

Is your second book already written?

It is written, and it is undergoing peer reviews. In Sha’allah, we will get the decision on its faith. If case peer reviewers and the editorial board are satisfied, it will be published by the State University of New York Press by the end of 2024.

You’ve already got there. Can you say that again about what you said about the books that are yet to be written as an engaging part? I love the way that you phrased that, and it’s very inspiring.

It was Tusak’s own approach. In one of his works, he points out the long and venerable history of the double metaphor of humans perceiving the whole world as a text and a text of a book, for instance, the text of the Quran as the world. The best way to approach this double metaphor or interpret it is to contribute to discussions by producing new books. This is what I tried to do with The Written World of God. You know what I mean about what I mentioned in the earlier discussions.

This book about the symbolism of the letters of the Arabic alphabet is something that I wanted to read since my student days, and I couldn’t because Professor William Chittick simply decided to abandon his project, the Breath of the All-Merciful. It took me several years to embark on this quest for knowledge and to gather determination to be the one who will be writing books that I always wanted to read and couldn’t because they are simply yet to be written.

This is what I’m doing. My second book was on Jinn devils and the problem of evil in Akbarian Sufism. I’m gathering and interpreting the stories of the many adventures of the Jinn book in the Islamic normative tradition, in poetry books, literature, and in the works of Ibn Arabi and his students and followers. That’s the case with my third book which goes into the symbolism of the letter Alif, the symbolism of the night, or the term Leila meant for Ibn Arabi and night rituals.

That’s so deep. It seems like every letter has a book in it. As you find in his books, usually, the work is distributed along his books. To collect them in one book about one certain topic seems a wonderful approach that will do great service for the people who love to read his book and contemplate it.

When you are interpreting his books, are you relying a little bit also on science and modern discoveries in different fields such as Psychology or Physics, or do you convey what he means in the unseen realm?

I am an inspiring scholar in Islamic studies, and my specialization is in the history of Islamic philosophy. My methodology approach is colored and determined by my academic training and academic credentials in the same way as anthropologists and ethnographers probably prefer a more hands-on approach to contemporary reforms of Akbarian Sufism.

I was also reminded by your remarks and comments on another thing, and that is that Ibn Arabi himself wrote specific books and treatises dedicated to one of the letters of the Arabic alphabet. Some of these have even been translated into English like his book of the letter Alif and book of the letter Baa, which were both published in the journal of Ibn Arabi Society for those who are interested in seeing how Ibn Arabi himself approaches individual letters of the alphabet.

He touches in his work on Psychology, Philosophy, and Science altogether. He is multi-layered like that.

It is something I once heard during a group discussion by the members of the Ibn Arabi Society that Ibn Arabi is not far from anything in life. His writing opus is so big. The topics he covers are so diverse that Islamologist can research almost anything they want by focusing on Ibn Arabi’s works.

For example, one of my forthcoming projects will be dedicated to Ibn Arabi’s notion of food and eating special types of food on specific culinary recipes to gain spiritual insights and spiritual knowledge. We have letters, art, Metaphysics, Ontology, the study of the Quran, natural history, Jinn night, culinary recipes, and even poetry.

He’s a whole human being.

I don’t feel so bad because I have a real interest in all of those things, and I have a special interest in food as well. I feel like I’m always flip-flopping back and forth between those topics, and so now I don’t feel like them all.

I’m not anywhere to the degree of where Ibn Arabi is in the depth of it, but now I feel a little bit better about myself that I’m not the only one that flip-flops back and forth as a spiritual approach to all those various topics. I have also had a great passion to look into food, body, and spirituality. One of the first summits that I ever did was the food, body, and spirit connection. I look forward to reading that book.

It’s more of a paper, as a matter of fact. I’m hoping to publish it.

If there was a way that I could read it, I would.

I will aim to publish it as soon as it’s done.

I want to make sure I’m following so I see that when it comes out. I have a question about something that I was reading in your book about letters. I want to bring up some of the specifics of the topic for people who are brand-new to this topic. You talk about the letters having some consciousness and meanings. Each one is a book in itself.

You were talking about the letters in terms of the four matters, the hot, cold, dry, and moist, and that the letters have properties. As they combine the different combinations, the matters produce different things. As I was reading this, I was perhaps getting a sense of how a vibration of sound with a spoken word with an intention can start to have some translation into physicality in this 3D world. Could you say a little bit more about that?

Perhaps it would be easier to refer the readers to a new course, to the forthcoming journal of Ibn Arabi Society. The transformation of the letters of the Arabic alphabet matters. Organic and inorganic is one of the most complex topics that I ever encountered in Ibn Arabi’s books. Among other things, it includes a four-page of mathematical calculations, one diagram, and two others that I tried to draw myself to illustrate the process.

Ibn Arabi figuratively compares this process to the writing of the book. Letters have different properties, including properties like hot, cold, dry, and moist, which Ibn Arabi refers to inform others that we then form to create the so-called four elements, fire, water, air, and earth. All things in existence Ibn Arabi believed are made of these four elements in different combinations in order to make different forms of existence.

He did try to explain this process in detail with mathematical calculations. I don’t want to brag, but I believe I even found a mistake in these calculations because the numbers, at one point, don’t add up to what the text explains. It is a complex system that I try to make sense of in a paper that will be published in a spring edition of this journal.

Did you find that in the material in itself or another context?

It is in Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyah especially concentrated in chapters 2, 60, and 198. There are other works going into letters and the properties of letters, especially Kitab Alif, the book of baa, and several others which are listed on one of the first pages of my book. I tried to go through all of this material as I was writing the book.

I tried to look beyond Al-Futuhat because in spite of the fact that Ibn Arabi says that the core of all of his teachings is gathered in Al-Futuhat, one can get a pretty comprehensive overview by reading this huge works. I believe that the devil is in the detail and that works, books, and papers should be rich in school. I try to amass as many details as I couldn’t present them to the reader with my own personal interpretations of these teachings.

It is not a definite interpretation. I don’t believe that anyone can give a definite judgment or interpretation of works that are as rich and often seemingly mutually contradictional as Ibn Arabi. In the end, Akbarians often quote the brethren of purity, a quote reading, “God loves those who seek perfection in their own works.” This is what I try to do, to approach perfection as much as I can.

If you look at even the arguments between science, religion, and art as the broader topics and how they seem to contradict each other yet in a deep way all lead to uncovering the same body of knowledge, to me, it’s no surprise that you would find contradictions within that complex and expansive body of work because that’s everywhere.

Looking from a different perspective, if you are looking at Cosmology differently than Psychology, together they integrate to give us a better view of reality, which we can only approach but know in a perfect way. We can approach that perfection. We should aspire to always do that. Ibn Arabi also talks about the relationship between the letters and the planet. In your interpretation, how did he come to that conclusion? What does it mean?

I would like to address one other thing you said about contradictions. They have long confused specialists in the field. One of his interpreters even said, “That’s the way things are supposed to be. All these people believe in the same God but have different notions of him.” It is very easy to find confirmation of one’s ideas in Ibn Arabi’s works.

Seemingly finding confirmation, to your theories which direct quotes, this is something that Ibn Arabi said, but he also said something else seemingly completely contradicts the quote. You found such a quote seemingly mutually, contradictory, and confused scholars.

My personal approach is that the same one that William Chittick had was to give two quotes, a contradiction, one quote next to one another for people to also interpret for themselves alongside my interpretation.

With regard to your second question about connections between the letters and the planet, he doesn’t speak about this very connection. He rather associates one letter of the Arabic alphabet with heavenly spheres. Ibn Arabi’s works have a system based on the teachings of Thalami which were adopted by Sufis around the eleventh century.

Ibn Arabi’s diagrams do teach the planet Earth is surrounded by seven planetary spheres and two other spheres. He envisioned that planets swim in those spheres, which then surround the Earth. When he associates the letters with them, he associates it with the whole sphere, not just with the planet. He speaks of the 28 levels of existence corresponding to the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet. Seven of these letters correspond to the planetary spheres.

To make things more complicated, he also speaks about the rotation of the spheres, which creates the letters of the Arabic alphabet. This is a process I tried to illustrate in my forthcoming paper. It is a very complex topic, especially since I also tried in my previous paper to write about the music of the spheres and how Ibn Arabi interpreted this concept.

In any case, it is a complex topic. I believe that the solution lies in the fact that he believed it is the Breath of the All-Merciful, the creative force of God, which spins the heavenly spheres, forcing them to rotate. He associated this breath with the letters themselves were to the act of speaking which might serve to explain this connection which he never elaborated on in great detail in his works.

It’s one of his most mysterious works because he doesn’t talk about it in detail.

He does not, and it’s curious because he also gives his reasons. His resolve was formed not because he feared that the uninitiated might misuse the power of letters to achieve selfish goals. Ibn Arabi also feared the loss of reputation. Those fears were justified. We can see it in the works of Ibn Khaldun mere centuries later how even Khaldun writes about evil Sufis and founders of the Islamic science of the letters.

Mere centuries later, we don’t see the signs of the letters as the divine science or the holy signs of wise men and God’s friends. We see it being associated with magicians, with people who corrupt and resort to dubious methods to achieve their goals. Probably similar associations already existed as early as the thirteenth century when Ibn Arabi wrote.

He doesn’t say, “I want to protect people from themselves or from getting hurt by using the power of letters in the way they shouldn’t be used. I also need to protect myself and my own reputation if people were to try to put into practice things that they read in my works, and then they don’t work. That’s ruining my reputation by proclaiming me a fraud.”

He had fears for his own reputation, which is one of the reasons he avoided this seemingly controversial topic. It’s interesting because he claims all he ever wrote, he wrote as a result of the divine revelation. It was almost to the direct order of God in using him to write.

Still, he says, “If it weren’t for the fact that Ibn Barrajan put some of his teachings about the letters or into his written works, I wouldn’t have refrained from writing a single thing about them.” He would have opposed this direct divine decree out of fear. He feared the letters. He feared for himself and his reputation.

It brings me a question because you also write about these things. Have you also feared certain readers coming across your book that was not in your mind?

I am an aspiring scholar who is hoping to one day get a tenure-track position in academia. I often wonder with that goal in mind whether I have chosen the wrong topic. By that, I don’t mean the letters or the symbolism of the letters or the topics of my next works like the problem of evil, but Sufism itself. I did encounter very judgmental comments about Sufism itself when I was doing my PhD and contemplating my next steps.

For example, I had one of my supervisors tell me that experts in Islamic studies focusing on Sufism only understand each other when they speak about their nonsense. I often wonder whether I made a mistake with those career goals in mind, but then, I also believe it is the topic that chooses the brighter and not the other way around.

Writing is a long and painful process. There is a painstaking years’ long research process. There is a writing process, and once again, a publication process and a peer review process that takes years. I don’t think one could go through all of these steps if not for the great love, joy, and happiness one finds in writing and in different topics that, for some reason, resonate with us.

That helps you to overcome the fear. It’s highly respectful that you are standing for your call and your passion in spite of the resistance you might find in the academic field or outside. You will also find people who are passionate about that work and will certainly benefit from your research. Contradictions always exist.

Not to mention that I am researching the works of the scholar to whom Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy refers to possibly the greatest of all Muslim philosophers. There is resistance not to Sufism but to topics that are not very modern, the thirteenth century. Why the need to go so deep into the past?

I believe that one needs to go to the past in order to understand the present. I don’t think those are exaggerations when academic works divide the history of Sufism and sometimes even the history of Islamic civilization to the period before and after Ibn Arabi.

His works left a deep and lasting impact on culture, philosophy, literature, and poetry, influencing the lives and works of scholars in the centuries ahead. It is a great joy to be able to find new topics, perspectives, and research aspects of his works that I can bring to light. It is a source of great happiness and joy for me, and a great motivation to carry on as before in the years ahead.

It reminds me of the hidden treasure that desires to be known and needs the treasure chest in order to be opened for that treasure to be found.

It’s another barrier now. It’s a deeply Akbarian thought that says, “If you weren’t meant for perfection, that means you wouldn’t be yearning for it, either.” Maybe we were always meant to be the writers of the books we have written. Perhaps it was always meant to be.

I want to ask one more question about something you said. You mentioned the music of the heavenly spheres. I’m wondering if you can say a little bit more about that.

I published a paper on the topic and a special addition to a religious journal dedicated to Ibn Arabi. Music of the spheres is a concept Ibn Arabi adopted from Pythagoras and Greek philosophy in general. Music of the spheres is the term usually used to describe the sounds of the heavenly spheres rotating and interacting with one another.

I originally approached the topic with hopes that it will turn into a book where I will get to find evidence indicating this music is the sound of the creative word of God bringing the universe into existence. This is not how it happened, but life is full of surprises. Ibn Arabi rather associated the music of the spheres with prayer.

It did not have a very big influence on the spiritual practices of the Akbarians, but it was deeply associated with prostrating and prayer. In other words, there is a curious paragraph in Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya. Ibn Arabi says, “If you prostrate in prayer and recite from the Quran during the prayer, and you did not hear this glorious music ringing in your ears, then perhaps you did not prostrate as you should have.” Long story short, that is the main role of this heavenly music in Akbarian Sufism.

If you prostrate in prayer and recite from the Quran without hearing glorious music ringing in your ears, perhaps you did not prostrate as you should have. Share on XAmany, you were speaking of the instrument, oud.

The Arabic instrument oud, when you study its history, you learn that they have the tunes and so forth based on the science of the letters and the numbers to produce these harmonics. Also, the shape and everything or every part of that instrument have a name that carries a special meaning. It’s very interesting to find it ingrained in philosophers such Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina who wrote about music before Ibn Arabi and probably inspired him also.

Farabi invented a musical instrument. It is said he will make people cry or laugh with how he will produce his music. They had this knowledge and this passion. They were philosophers, physicians, and astronomers. That is the idea of Al-Insan al-Kamil, the complete, whole, or perfect human being who is well-rounded in all this knowledge and integrated with their life. It’s something we should aspire for because modern life has separated it in a way that is not healthy.

Hearing you say this, I realized what I said might be slightly confusing. Ibn Arabi was not among the scholars who denied the impact of the heavenly spheres on planet Earth. He believed in their existence. He believed they have an impact on Earth.

There are even hints from the Al-Futuhat that he, too, is the brethren of purity associated with the seven planetary spheres with the string. One sphere or string can be used to influence human bodily humor and produce an impact on the human body as well. What I meant to say is that these practices did not play a very big role in Akbarian Sufism. This is something I wanted to clarify.

Thank you for the clarification.

It’s all connected. Dunja, I’m noticing the time. You had a stop time that I want to respect. Amany, do you have any questions before we ask our final question?

No questions in particular. It was very nice talking to you.

I appreciate the invitation to the interview. As a writer, I am very interested in the reception of my own book. It is my personal rule never to google my own name on the internet. The impressions that I get are the letters and messages from readers and colleagues that I receive through the course of my email. I would like to ask you once you are finished with the readings and to tell me of your impressions. It’s more a small favor to ask than a question.

We are a lover of Ibn Arabi, and we are happy to come across your work and read it and write our feedback.

Thank you very much.

I’m already feeling like I’m going to read it at least three times and then I will let you know because I feel like I’m wanting to study the ocean, but now I’m at the foam on the surface. I know that there’s so much depth and so much contained in the ocean that is going to take a very long time if ever in a lifetime that it could be explored. I love the way you put things together in this book. I love the way it’s structured so far. Amany, go ahead.

My last question is this. Ibn Arabi’s work is originally in Arabic. Have you studied Arabic? Do you translate the work, or do you rely on other translations, and what would that be?

It is impossible to study Ibn Arabi’s translations of Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyya because this enormous work was not translated to date. There are several translations or several dozen maybe of his lesser works. Anca Publishing and Ibn Arabi Society made their mission to translate as many of his works as possible and make them available to the general public.

When it comes to Al-Futuhat, it was not translated completely to the date. Professor Chittick said, “I have never translated it simply because I never had a lifetime to devote to it.” There is a translation project ongoing, and it is published by PEERS press, but I think they only made it through eight books so far.

At this rate, it might take over a decade or two to at least the end of Al-Futuhat. Luckily, I study Arabic. I hold a bachelor, Master’s, and PhD in Islamic Studies. I did study the Arabic language. Otherwise, a great portion of his works for the major portion would be inaccessible to me.

That’s wonderful to know.

Any words of wisdom, encouragement, or direction that you would like to share with others who are interested in diving into this work to learn more about it, especially our younger generations? To me, the inspiration that I feel to dive into this is to understand the creation and how a spoken word can end up as this, a mouse that controls a computer. There’s a great curiosity that I have to understand the levels of consciousness and creation. Let me hand it over to you. Any thoughts, encouragement, or advice that you’d like to give?

I’m not sure if I am the right person to give advice to, having gained my PhD degree and being still in the search of a permanent academic position. I would perhaps advise the readers to follow their dreams. If they find something they care for so deeply, something that is a big source of joy for them as research and writing, pursue it to the very end in spite of the fact that both the letters and Akbarian Sufism, especially academia and careers in academia are precarious fields.

I would advise them to pursue their dreams because that is, I believe, the only possible way we can contribute something meaningful and deeply valuable for life. That is our contribution to the world. It’s possibly the only or the best way we can make that contribution. That is why I would advise people to have the courage to follow their dreams and passions to where they may lead them.

Follow your dreams and passions wherever they may lead you. This is the only possible way we can contribute to something deeply valuable for life. Share on XThat’s beautiful and inspiring. It gave me hope to see young people like you going into such a deep field of Ibn Arabi’s work. It gives me hope that there will be people who still carry that spiritual path and explain it in a way that hopefully can reach modern readers. It’s been a pleasure to be with you. I thank you very much for coming and spending this time with us. We hope to stay in touch and have you again in the future.

Please write me about your impressions of the book. I would love to hear them. Thank you very much for inviting me.

Thank you so much. In what you said in terms of following your inspiration and passion, as someone whom I believe I had a passion for this at a much younger age when I was in college and was diverted because I was not in the company of people who would understand what I was experiencing, and I didn’t have the language to communicate or the knowledge to know that there was even a pathway forward that I could keep going with it.

I want to add that to what you said because I wish I had heard that advice when I was in college and feeling what I was pursuing was not tangible enough to be sustained in the world. I appreciate that you shared that because here we are and we are back at it. I’m glad. This is my way of continuing and picking up however many years later in my college inspirations.

When I was at college, I perhaps made the mistake of graduating too soon. If I could go back in time, I would have extended my PhD studies to ten years if necessary, gaining more papers, publications, and more years of teaching experience because sometimes passion is not enough. Even being good at what you do and having great knowledge is not enough.

Academia is a precarious field, and one simply needs teaching experience and publications an unfair amount of both. In order to have a feasible career, because that is the only career possible, the way I feel that can sustain a regular writing practice that I’m aspiring to. That is something I wish I knew when I was a PhD student that I had someone to tell me that.

Don’t be in a hurry. You have your scholarship and a secure position. There is a big chasm between the number of PhD positions and assistant professor positions. There are so few postdoc positions in the field, and you will need so many publications and so much experience to ascent to make that big step between your PhD studies and a relatively secure working position and income in life. That is something I also wish I knew back then.

I can relate to what you and Debra said because when I was doing my Master’s degree, I found the academic field itself is not welcoming to some research or topics, and their approach to it as well. Even though I did try to get hired by universities, in the end, I made the decision that I will stop trying to apply to universities because I found that I didn’t like the environment. It was my blessing that God opened for me to be the translator for the Sufism Sheik Sidi Muhammad al-Jamal.

This opens me to a certain way to pursue and share my passion. Continue to be resistant in what you do and you are having joy in doing it. In one way or another, the door will be opened for you to share what you have and the knowledge you have, and you will find the people who will truly benefit from it and welcome it. I pray for the best for you. May God bless your work and give you the position and the place that will help you flourish in what you are doing.

Thank you for your kind words.

We are all students of life. One attitude or perception that we can choose is that even if we are no longer in formal studies, we can still be a student of life and continue to research and learn. Thank you so much, Dunja, for everything. I look forward to finishing this book, reading it two more times, and reading the other books that you have coming out, and the paper on food and culinary.

Fingers crossed.

I’m excited about all of it.

It sounds very interesting, for sure. Thank you.

Is there any way that you would recommend people who want to follow you somehow so that they can see when the other books are coming out and other publications are available? Is there a way for people to access you?

As I said, I have been consciously trying to keep my presence minimal. I know that will have to end this soon with a few of my papers coming out and the second book, hopefully. For now, for people who wish to contact me, I recommend them to do so via my email or social networks. In Sha’allah, relatively soon, I’m planning to open an academia page or a few more pages where I will upload my new books and papers.

Even though you don’t google yourself, we can google you and find you in the near future. Thank you both very much. For those of you reading, please stay tuned because there’s more to come. God willing, we’ll be able to have some continued connection with Dunja so we can follow her together. Thank you.

Important Links

- The Written World of God: The Cosmic Script and the Art of Ibn ‘Arabi

- Universal Chaplaincy

- The Ocean of Sound

- The Meccan Revelations

- Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyya

- Ibn Arabi Society

About Dunja Rasic

Dunja Rasic earned her Ph.D in Islamic Studies at the Free University Berlin. Her primary research field is medieval intellectual history, with a focus on Akbarian cosmology, philosophical Sufism and the Islamic philosophy of language. She is currently working on her second book, which is focusing on jinn doubles and the problem of evil in Akbarian Sufism.

Dunja Rasic earned her Ph.D in Islamic Studies at the Free University Berlin. Her primary research field is medieval intellectual history, with a focus on Akbarian cosmology, philosophical Sufism and the Islamic philosophy of language. She is currently working on her second book, which is focusing on jinn doubles and the problem of evil in Akbarian Sufism.